Finding Family in the Archives

Finding Family in the Archives

Introduction

The Notary in Question

William Stevens practised as a notary in Malta for nearly fifty years, from 1806 to 1854. He was the first of a small group of British notaries working on the island in the British Period, during a time of significant social and political change. In fact, this put him in a position to be able to record the activities of many mercantile and enterprising ventures by British and Maltese alike. His work was also extensive, but he was more than just a name and signature at the end of each deed.

As it turns out from his correspondence and those of his son William John Stevens, who followed in his father’s footsteps and became a notary in his own right, he and his wife, Giovanna, had fifteen children. The family was far-reaching, and travelled extensively, with his adult children working and raising their own children in Turkey, Ukraine, Iran, Azerbaijan, Georgia, England, India, Ireland, Brazil, and Saint Thomas in the Caribbean (now the US Virgin Islands). Stevens himself was even imprisoned briefly in 1833, a trial that became the talk of the town, full of personal and political intrigue.

The archive preserves dozens of volumes of notarial acts written by both father and son. In recent years, they have become the focus of a long-running research project by Sarah Watkinson, whose connection to the Stevens family began with a brush and a curiosity.

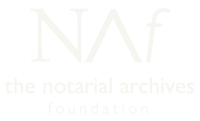

The cover of R450 Volume 2, of Notary William Stevens, 1821.

Discovery and Early Research

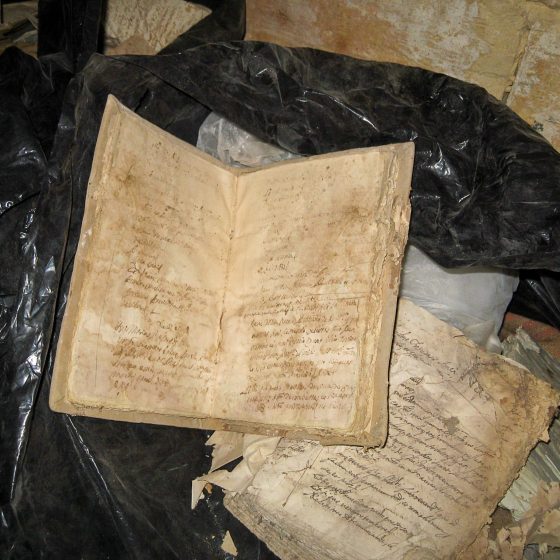

Sarah first visited the Notarial Archives in 2012, not long after moving to Malta. What she found was not a pristine research library, but a building in poor condition. The roof leaked, papers were stacked in boxes, and many of the rooms were filled with volumes in various states of disrepair. Despite this, or perhaps because of it, she felt drawn to the place. Encouraged by Dr Joan Abela, she began volunteering, carefully brushing dirt off centuries-old pages.

At first, she was frustrated. The early modern Italian was difficult to read, and her efforts to understand the handwriting led nowhere. Joan suggested she look at the English-language acts of the few British notaries who had worked in Malta during the 19th century. These included William Stevens, William John Stevens, and Charles Curry. With no catalogue in place, Sarah and a team of volunteers helped build a database.

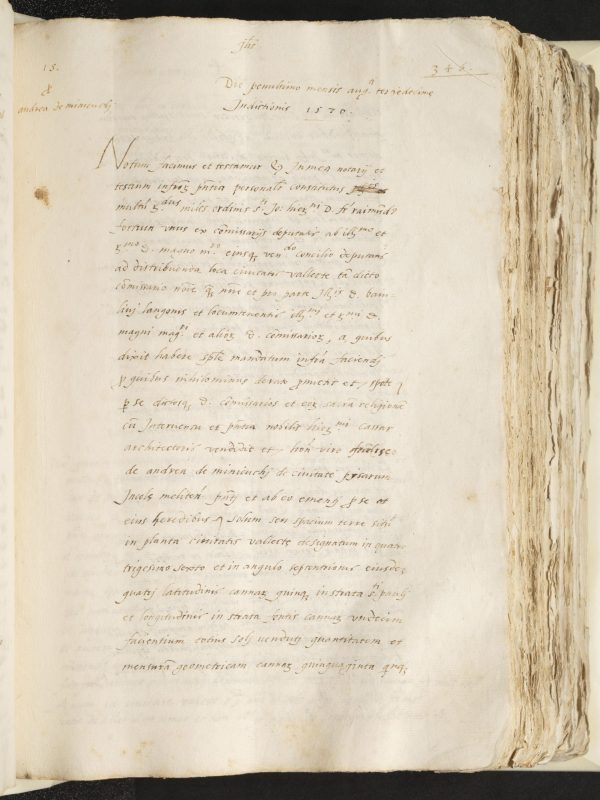

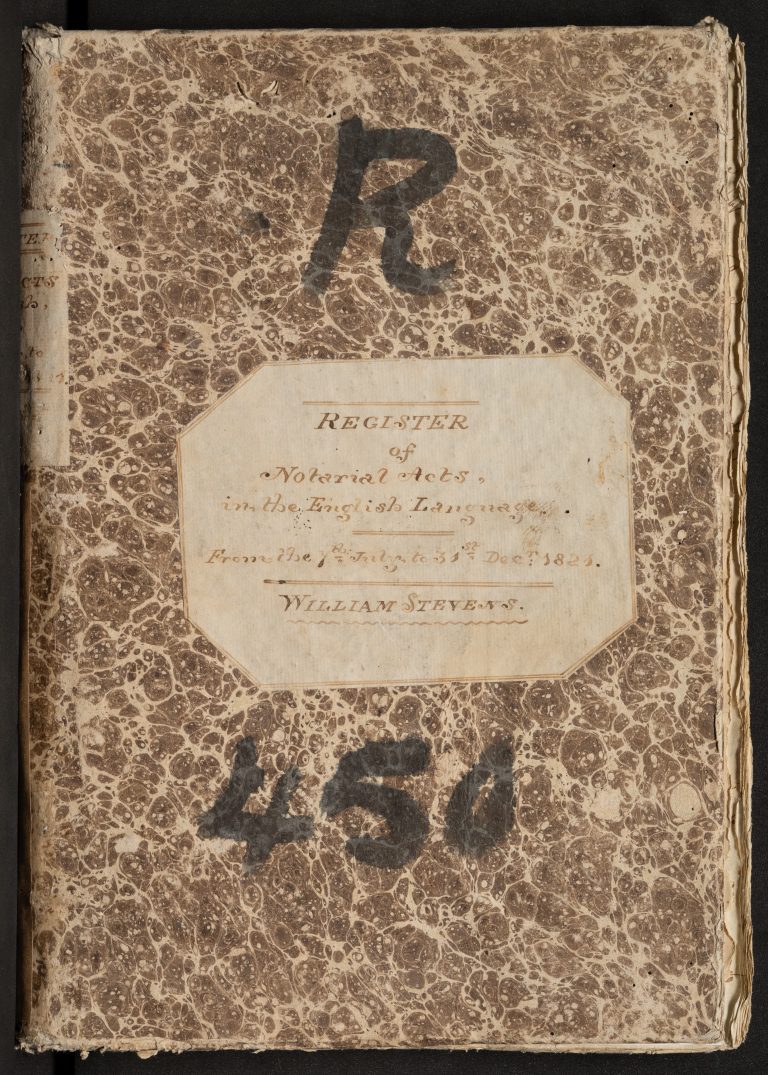

Title page of R451 volume 1, Notary William John Stevens (son of William Stevens), 1831–1832.

Seal of Notary William John Stevens, from R451 Volume 2, 1833.

They started with William John’s volumes, as the handwriting seemed more legible. The first document she read, about a ship quarantined in Messina, felt disappointingly mundane. But the second deed caught her attention. It was dated 1831 and had been drawn up to protect William’s wife, Giovanna, from an “embarrassment” caused by her husband seventeen years earlier. The act was prepared by one son and witnessed by another. It raised questions. Why record such a thing so long after the fact? What exactly had happened? And why did the family choose to document it in this way? From that moment, Sarah was drawn into the story of the Stevens family, and the deeper she went, the more there was to find.

Finding the Personal Documents

As the archive continued to be sorted and reorganised, Sarah came across boxes of loose documents. Among them were personal letters, notes, invoices, and scribbles written by William, William John, and other members of the family. These papers had likely been swept from an office desk after William John’s death. While the culprits are unknown, Sarah suspects his sisters. They were never meant for public reading, but for Sarah, they were a treasure trove.

The letters weren’t easy to read. Frederick, one of the sons, often wrote a full page, then turned the sheet sideways and wrote across it again to save paper. William John used extremely thin sheets that made the ink bleed through. The handwriting was messy. Spelling and punctuation were unpredictable. But what they revealed was remarkable. Here were the voices of a family that had lived across continents. Their joys, struggles, and daily routines were preserved in their own words.

These letters filled in the human details that the notarial acts had left out. They showed the emotional weight behind the legal documents. Sarah learned about the family’s travels, illnesses, arguments, and affections. And while she could not use these letters in her Master’s thesis, which focused on notarial content, they became the foundation of her forthcoming book instead.

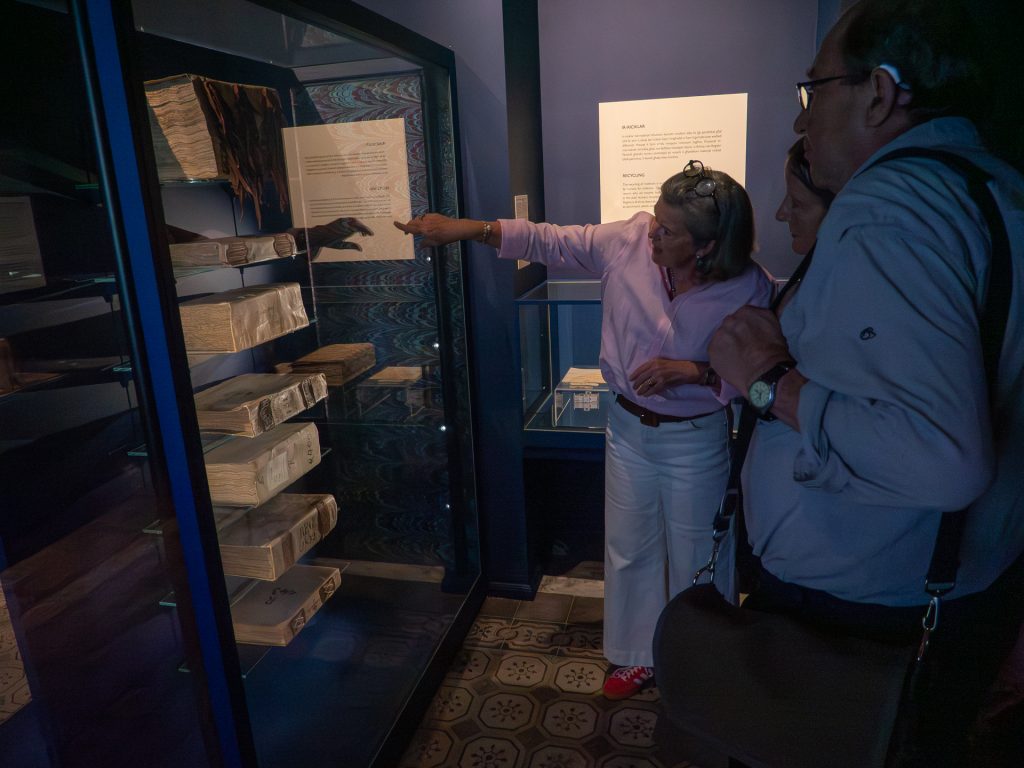

A Visit Across Generations

A recent visit by descendants of William Stevens took place at the Notarial Registers Archive, where they viewed a selection of original documents linked to their ancestor’s notarial work. While it wasn’t the first time Sarah had met them, the timing carried a particular weight. With her book on William Stevens’ personal life nearing publication, the opportunity to share parts of the original material with his descendants felt especially significant.

The fact that a notarial attestation written in the 1800s could still hold personal meaning for his family in 2025 speaks to the lasting human relevance of these records. It also highlights the vital role of the archive, not just as a legal repository, but as a space where history remains connected to the present and open to discovery, interpretation, and even human connection. It also aptly demonstrates that the notary himself—his professional life, personal life, and relationships, and the networks in which he moved—is a valid subject of interest and research in his own right.

“People often assume legal records are dry or impersonal,” Sarah reflects. “But they can be incredibly rich when you know how to read them. Notaries didn’t just passively record legal transactions or events, but were active parts of those societies, with their own opinions, families, and conflicts. And all of that shows up in the margins, in the choices they made, in what they chose to record, and in the miscellanea that never made it onto the notarial acts.”

Photos from the recent visits of William Stevens’ descendants, together with Sarah Watkinson.

A Living Archive, A Knowledge Trove

The story of William Stevens and his descendants is just one example of the kind of research that can come out of the Notarial Registers Archive. The archive holds thousands of volumes, many of which have yet to be fully explored. They contain records of marriages, debts, adoptions, business dealings, dowries, and disputes. But they also contain human moments. Behind every legal formula is a person. And behind every signature is a story.

For students, researchers, and scholars alike, the Notarial Registers Archive offers a rich and largely untapped field of study. Whether your interest lies in history, law, gender, migration, social relationships, or material culture, there is something here for you.

And sometimes, as Sarah’s work has shown, the story you end up telling is more surprising, more layered, and more personal than you could ever have planned.